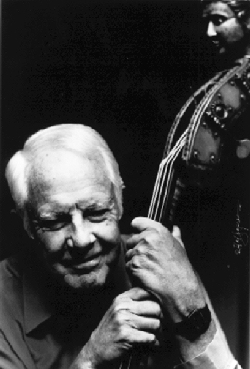

A Musician and Composer

Robert Sherwood Haggart, bassist, composer, bandleader, was born in New York City on March 13th, 1914, and died in Venice, Florida on December 2nd, 1998. He grew up in Douglas Manor.

The following article is by Steve Voce. This article first appeared in The Independent, the British national newspaper, and is reproduced here.

“He could have been another George Gershwin if he’d channeled all his talents into composing,” said Bob Crosby. “The man himself will never realize just what talents he possesses,” confirmed Eddie Miller.

Both men, colleagues of Haggart’s in the co-operative Bob Crosby Orchestra, were talking of Bob Haggart, a multi-talented musician if ever there was one, composer of the classic What’s New? and a multitude of good tunes. It seemed unreal that a man so gifted should be happy to confine himself mainly to playing the double bass in support of other soloists but, for 70 years, that is what he chose to do. Yet, as well as his brilliance as a composer, Haggart could have been amongst the finest jazz guitar players and also excelled on trumpet and at the piano before settling for his modest role in the rhythm section.

He had an unusually varied 70-year career whose many highlights included recording with Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Duke Ellington and Charlie Parker. Often he wrote the music for the sessions as well. A founder member in 1935, he was the last survivor of the Crosby orchestra, one of the outstanding bands of the Swing Era.

He was raised in Douglaston, New York, celebrated by his Dogtown Blues, a composition featured by the Crosby band on one of its most popular recordings.

Haggart was given a banjo-ukelele for his 13th birthday. He was too polite to point out to his parents that he disliked the sound of the instrument, but an indulgent mother soon bought him a guitar. He took weekly lessons from the master guitarist George Van Eps and soon was invited to play in the family jam sessions with which the Van Eps home resounded. Van Eps was later to persuade Artie Shaw to audition Haggart on guitar for his band.

The young Haggart also played tuba in the school band. Weary of carrying the huge instrument to summer camp, he applied for and got the job of bugler at the camp. This led him to buy a cornet, which he took with him when he enrolled at the expensive Salisbury School in Connecticut. The school was known to be a “snob factory”. Haggart became a founder member of the Salisbury Serenaders, the school dance band, and soon began to modify the printed stock arrangements that were bought for the band from the local music shop. He re-wrote complete sections of these, and eventually began writing his own orchestrations from scratch.

Doubling on cornet and guitar, Haggart persuaded his mother to pay for a trumpet when he left the school in 1929.

“I always have a soft spot for the guitar. My very first gigs were as a guitarist with drummer Fred Petry’s Happy Daze Orchestra. Fred took the name from a big picture he’d cut from a Saturday Evening Post that showed a drunk with the caption ‘Happy Daze’. Fred had no foot pedal and used to kick his bass drum with a sneaker.” Petry later went on to play for the bands of Artie Shaw and Jack Teagarden. It was at his home that Haggart first heard jazz, on a 78 featuring the cornetist Bix Beiderbecke called Singing The Blues. He soon bought his first jazz record, Louis Armstrong’s I Can’t Give You Anything But Love.

“That one turned my life around. I guess if I had never heard jazz like that I might have become a hosiery salesman like my father.” Until his death Haggart liked little better than the chance to discuss the magnificence of Armstrong’s early recordings.

Now enrolled at the Great Neck High School, he saw a double bass leaning against the wall in the school’s music room and asked the teacher if he could play it. He never looked back, and word soon spread of his great abilities to swing a band with the instrument.

After Haggart had bought his own bass, his talents earned him an invitation in 1933 to play a ten week season at the British Colonial Club in Nassau. During the voyage rough weather caused the ship’s piano to roll and to turn the bass to matchwood.

For the next three years he worked with a variety of local groups and each year played the season in Nassau. By 1935 he had been offered jobs by both Tommy Dorsey and Benny Goodman, but turned them both down.

Glenn Miller and Ray McKinley, both by then with their own bands, recommended Haggart to the embryo Crosby band. He liked the idea, joined and, as a pivotal member of the rhythm section, shot to national fame as the band took off. With its free spirit the band captured the imagination of the youth of the Thirties. Haggart soon became famous not just for his bass playing, but also for the imaginative arrangements and compositions that he wrote for the band. One of his early successes was also the biggest. There was a nucleus of musicians from New Orleans in the band and one of them, drummer Ray Bauduc, hummed some phrases to Haggart that he remembered hearing New Orleans marching bands play. Haggart worked them together and the result was South Rampart Street Parade. This, recorded in 1937, became an immediate hit and was featured on the band’s many broadcasts and theatre concerts. It is still the number for which the band is best remembered.

It was as an afterthought at the end of another recording session by the band a year later that Haggart and Bauduc recorded a strange duet that they had featured at dances. Haggart whistled through his teeth and plucked the bass fingerboard with one hand whilst Bauduc played on the strings near the bridge of the instrument with his drumsticks. The eccentric result was called The Big Noise From Winnetka and it immediately became one of the band’s greatest hits. One radio station played the record 22 times in a single day.

Another trumpeter, Billy Butterfield, played the solo on a new ballad Haggart had written that was recorded on the same day. It was then called I’m Free. Later, with added lyrics by Johnny Burke, it became What’s New?. Over the years it made a lot of money for its composer. “I just wish,” mused Haggart on one occasion, “that Barbra Streisand had recorded it. Think of the royalties.” He almost got his wish. A couple of years later Linda Ronstadt had a hit with her recording of the tune. By 1937 Haggart took first place in the Metronome poll, the earliest of many popularity polls that he was to win as the best jazz bass player.

In March, 1938 he married Helen Frey, who he had met at a dance the band was playing at. They stayed together until her death in 1994.

Haggart’s natural talents were too wide-ranging for him to find fulfillment within the Crosby band. When the band broke up in 1942 to work he settled in New York.

“I decided to put my bass in the corner and devote my time to arranging. I studied harmony, theory and all aspects of composition with Stefan Wolpe and Tibor Serly.” He worked as a writer in radio, the recording studios and television. A tutor for bass that Haggart wrote at this time became a standard text for the instrument. He arranged and played for sessions recorded by Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong for the Decca company, and both Armstrong and Duke Ellington called on him when they needed a bassist. He played bass at Armstrong’s classic New York Town Hall concert in 1947. He worked for the string ensemble that worked with the alto saxophonist Charlie Parker and also wrote for the large orchestras that backed Sarah Vaughan.

From 1951 to 1960 he led the Lawson-Haggart Jazz Band with his friend from the Crosby band, trumpeter Yank Lawson. The band took its music from the classic jazz repertoire of the Twenties. He and Lawson both worked for Louis Armstrong in the ambitious collection of recordings done as Satchmo – A Musical Autobiography in 1957. Heavy drinking had been even more a feature of life in the Crosby group than it had been in most big bands, and the habit had become an ingrained problem for Haggart and his wife by the Fifties. They both became teetotalers in 1956.

Nelson Riddle wrote the liner note for a 1958 recording of Porgy and Bess played by a large studio band led by Haggart. The scoring of this music was the achievement that Haggart was most proud of, but because of contractual difficulties his name was not mentioned anywhere on the album, and the public assumed that the music was the work of Riddle. He was pleased, soon after, when, their paths crossing at an airport, Gerry Mulligan ran over to him to say that he thought the writing on the album was magnificent.

He and Lawson were often called upon to play at Bob Crosby band reunions. Realizing that the music still had a following the two came out of semi-retirement in 1968 to form another band. It was funded by a millionaire called Barker Hickox, who chose the name for it that was so often to make the leaders blush – The World’s Greatest Jazz Band. With no trouble, Haggart rattled off 35 arrangements to get the band started. Over its ten-year existence the band, often featuring ex-Crosby musicians, made a succession of tasteful recordings.

After the group disbanded the two leaders continued to work together at festivals and clubs, and Haggart remained much in demand to back younger jazz stars like Bob Wilber, Kenny Davern and Randy Sandke. In July 1996 he toured Japan with a version of the World’s Greatest Jazz Band made up from these players and he had been due to play at the Edinburgh and Brecon festivals this year, but poor health compelled him to abandon the booking.

He spent his spare time painting, being gifted in both water colors and oils.

He is survived by his musician son, Bob Haggart Jr.