History | Maps | Photos | Neighborhood Highlights | Notable Residents | Building Survey | Public Events | Newspaper Articles

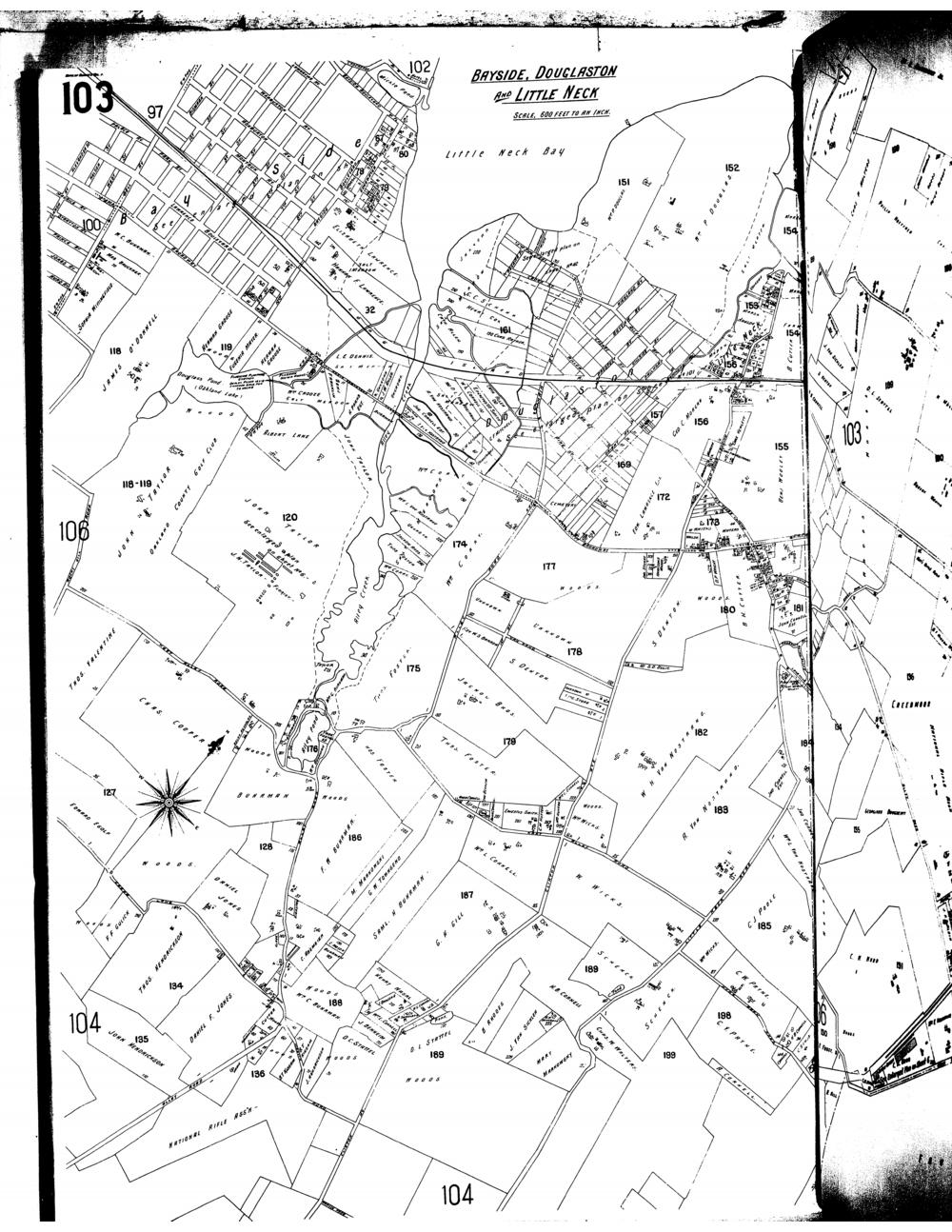

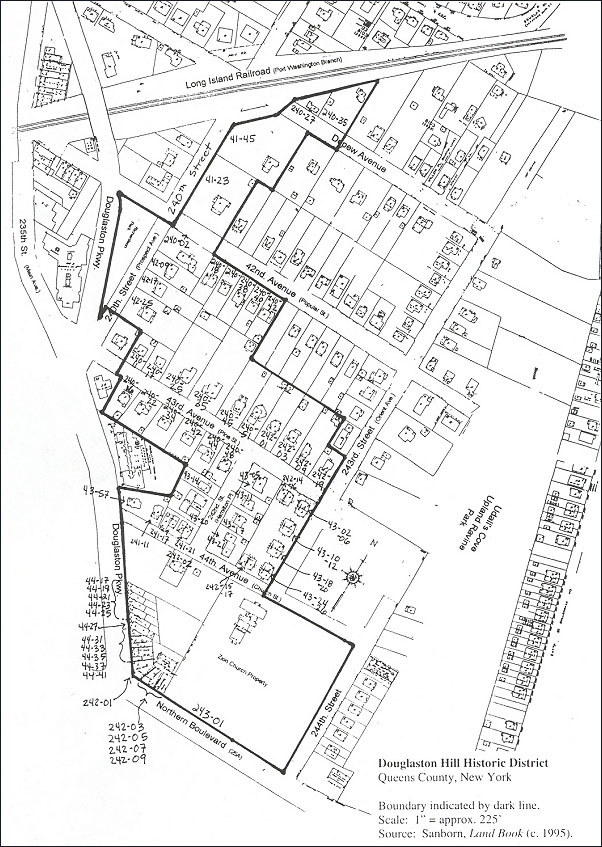

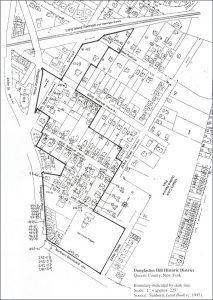

The landmarked Douglaston Hill Historic District is located in northeastern Queens County, New York, near the border with Nassau County. Roughly, the district is bounded on the north by the Long Island Railroad; on the south by Northern Boulevard, a major county thoroughfare; on the west by Douglaston Parkway, a main street in the immediate area; and on the east by Udall’s Cove Upland Ravine Park, a natural area.

The district’s boundaries follow the basic configuration of the street grid, encompassing the blocks of 44th Avenue, 43rd Avenue, the southeastern half of 42nd Avenue and the southeastern end of Depew Avenue — between Douglaston Parkway and 243rd Street (along the edge of Udall’s Cove).

Boundary Justification

The neighborhood of Douglaston Hill is bounded on the east and west by two prominent natural wetlands of northeastern Queens Alley Pond Park and Udall’s Cove Park. The neighborhood is bounded on the north and south by the Long Island Railroad (in place since 1867) and Northern Boulevard (a major Queens thoroughfare for more than a century). These boundaries reflect the natural and human development patterns of northeastern Queens.

Within that long-held neighborhood boundary, the Historic District boundary is drawn to reflect the natural and human development patterns in northeastern Queens. The District encompasses those features which best reflect the area’s historic development. The District fans out in a northwesterly direction from Zion Episcopal Church, with the northeast quadrant of the neighborhood omitted from the District. That quadrant comprises many houses built after the District’s period of significance (1900 to 1930), as well as a number of houses that are heavily altered. While there are some physical features within this area that reflect Douglaston Hill’s significance, as a whole, this quadrant does not retain the same level of integrity as the Historic District section.

Specifically, the district runs from the corner of 244th Street and Northern Boulevard west to Douglaston Parkway; north on Douglaston Parkway to approximately 62 feet (along property line of Lot 21, Block 8107) north of 44th Avenue; east approximately 166 feet (along the rear property lines of Lots 21 and 231 of Block 8107); north approximately 100 feet (along the rear property lines of Lots 214 and 212 of Block 8107); west approximately 288 feet (along the rear property lines of Lots 46, 43, 40, 38 of Block 8107); north approximately 116 feet (along the property line of Lot 38, Block 8107); west approximately 60 feet along 43rd Avenue; north approximately 100 feet (along the property line of Lot 81, Block 8106); east to Douglaston Parkway; north along the edge of the Catherine Turner Richardson Park; east to 240th Street; north across Depew Avenue to edge of Long Island Railroad cut; east approximately 270 feet (along rear property line of Lots 25 and 21, Block 8103).

History, Origins and Significance

The proposed Douglaston Hill Historic District, located in northeastern Queens (a borough of New York City) near the border with Nassau County, is significant in the area of community planning and development and as an example of a turn-of-the-century suburb. The district consists of substantial single-family homes, multi-family apartment buildings, commercial buildings, a small park and a church and cemetery. It is architecturally noteworthy for its many fine examples of late nineteenth and early twentieth century styles including Colonial Revival, Queen Anne, Shingle Style, Tudor Revival, Prairie Style and American Craftsman designs.

In its park-like setting, architectural expression and social history, Douglaston Hill is representative of the evolution of the commuter suburb. Within that context, the Hill, which developed over a period of eighty years, can be interpreted both as a precursor to the planned suburban enclaves of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (such as the adjacent Douglas Manor and the renowned Forest Hills Gardens) and as evidence of the speculative suburban development which remade the borough of Queens in the 1920s and 1930s.

The transformation of Queens from colonial villages to estates and small farms to commuter suburbs is typical of American settlement patterns in many parts of the country. The dramatic spatial change that this pattern of growth brought about — and the parallel development of a quintessential American lifestyle — were due to several factors. Rapid advances in transportation, particularly the steam railroad in the first half of the nineteenth century, made long-distance commuting possible. New levels of personal wealth following the Civil War, coupled with the pervasive cultural values of mainstream Victorian society, gave rise to a middle class that embraced virtues of domesticity, home ownership and life in a sylvan setting.1 These values were made manifest in the commuter suburb, a distinct form of community building which places the single-family house in a non-urban setting, convenient to the city by rail.

By 1939 the Federal Writers’ Project New York City Guide had designated Queens the “borough of homes,” a result of some fifty years of intensive speculative, mostly suburban, housing development.2 This development had its roots in planned developments of the 1870s and was greatly accelerated by the consolidation of New York City in 1898 — specifically by the public transportation improvements, large-scale middle-class migration and public works it brought to the new Borough of Queens.3

Within the boundaries of Douglaston Hill today, this history of community planning and development, from the 1850s to the 1930s, can be read in the district’s topography, layout, architectural expression and historic street names. The boundaries of the proposed Historic District encompass that section of the Hill which retains a relatively high level of integrity of location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling and association.

Regional Development

By the mid-1600s, several English and Dutch colonial towns had been established in what is now northeastern Queens. The settlers farmed and raised livestock in and around Mespat (Maspeth), founded in 1642, Vlissingen (Flushing), founded in 1643, and Jamaica, founded in 1650.4 Colonial settlement along the northeastern shore began near Alley Pond in 1647, and a decade later when, in 1656, the Dutch assigned to Thomas Hicks a peninsula then called “Little Madman’s Neck,” which encompassed much of present-day Douglaston. Hicks is best remembered for his “eviction” of the Matinecoc Indian tribe from its fishing grounds on Little Neck Bay in the 1660s.5

By 1683, when Queens County was established as one of ten English counties, these colonial settlements were thriving villages. The county was then divided into five “towns”: Newtown, Jamaica, Flushing, Hempstead, and Oyster Bay.6 The Alley Pond settlement (including present-day Douglaston lay within the town of Flushing. Farming was the primary use of the land, with a few large families the predominant property owners. The years prior to the Revolutionary War saw more estates built in the area, including the Cornelius Van Wyck House of 1735 (located within today’s Douglas Manor and a designated New York City Landmark).

Most residents of Queens were loyal to the British throughout the Revolution. Consequently, the county was under British occupation for seven years, serving as a major staging ground for British troops; and after the war, as a staging ground for the evacuation of loyalists. By the war’s end in 1783, the county’s once extensive tracts of primeval forest had been devastated and many farms pillaged by British soldiers.7

Recovery and growth were slow in the first half of the nineteenth century, but transportation improvements led the way for future settlements. Six turnpikes were built in the 1810s, improving farmers’ access to urban markets, and the Long Island Railroad began running from Brooklyn to Jamaica, Queens in 1836. The 1850s and 1860s saw large numbers of working class German and Irish immigrants settle in the industrial sections of western Queens; at the same time the “gold coast” of the north shore began to be a haven for the country homes of wealthy New Yorkers, along the coasts of Ravenswood, Flushing, Bayside and Douglaston, and into present-day Nassau County.

The Civil War catalyzed another wave of development and settlement in the 1860s and 1870s, when a number of large farms were transformed to development sites and whole villages were laid out. Richmond Hill (1869), Long Island City (1872), Bayside (1872) and South Flushing (1873) were all created in this way. In the decades leading up to the 1898 consolidation of the City of New York, most areas of Queens which were accessible were being developed.8

Two major public works were completed in the first decade after consolidation: the Queensborough Bridge opened in 1909; and the Pennsylvania Railroad completed tunnels under the East River in 1910. Rapid access for the masses brought increased industrialization and intensive housing development, and by 1930 the borough’s population had quadrupled and the assessed real estate value had multiplied sixfold.9

Origins of Douglaston Hill

In 1813 the peninsula estate on Little Neck Bay passed to prominent New Yorker Wynant Van Zandt III. Van Zandt had been an Alderman of New York City and a Vestryman of Manhattan’s Trinity Church before retiring to Little Neck as a gentleman farmer. He built a large mansion in 1819 (which survives as the Douglaston Club, and is a designated New York City Landmark).10 When Van Zandt arrived at Little Neck, there existed a community of gentlemen farmers, small “truck” farmers, merchants, artisans and oystermen. Its center was the Alley Pond settlement, considered in local histories to be the birthplace of Bayside, Douglaston and Little Neck. The narrow roadway that ran along Alley Pond was the primary route from Flushing to points east; thus the first Flushing post office was located at the Alley in the 1820s. The post office, along with a mill (dating to the 1750s), a blacksmith shop and a general store (dating to 1821) became the village common — from which farm produce and wood were shipped to New York.11

Van Zandt took an active interest in the civic affairs of the community centered around Alley Pond. In 1824, he financed the construction of a causeway across the marsh, creating a more direct and efficient route to Flushing.12 His deepest impression on the Douglaston area was his bequest, made in 1829, of land upon which to build a church and funds with which to build it.

For some years, Van Zandt had driven to Christ Church at Cow Neck (now Manhasset, Long Island), where his brother-in-law served as Rector. At that Rector’s transfer out of the Cow Neck parish, Van Zandt conspired to build a church for Little Neck. More than twenty men pledged further funds, and less wealthy members of the community pledged their labor, including a local painter and blacksmith, along with farm boys who made shingles. Douglaston Station was dedicated in 1830 by Bishop William Henry Hobart of the Protestant Episcopal Church of New York. Bloodgood Haviland Cutter, known as the “Long Island Farmer Poet,” remembers the church construction as a young boy:

“When the church frame was completed, I remember a great preparation was made to raise the frame…A great many gathered and helped raise our Zion frame…In the evening we had a good old-time feast with great rejoicing for the success in getting up the frame without accident. That was kept up till late at night.”

Since its inception, Zion has served in the tradition of the 18th-century New England Meetinghouse, as a center of religious and social activity for a far-flung community of farmers. Land for Zion’s cemetery was donated in 1834 and again in 1885. (This original building was destroyed by fire in 1924 and rebuilt shortly thereafter.)13

A few years after the death of Wynant Van Zandt in 1831, the Van Zandt family sold its estate. The waterfront peninsula portion of the property (what was to become Douglas Manor) was sold to George Douglas, described in the deed of sale as a “Gentleman.”14 The portion to the south, encompassing what was to become Douglaston Hill, was sold in 1834 to Joseph DeForest. DeForest sold the hill property one year later to Cortland Van Beuren, who sold it in 1843 to local farmer Jeremiah Lambertson. Lambertson held the property intact until 1853, when he laid it out in lots in an urban grid and sold them at auction.

George Douglas held the peninsula property until 1862, when at his death, his son William P. Douglas inherited the estate. In the tradition of gentleman farmer, William was active in local affairs, at Zion Church, as well as in supporting community-wide improvements. During William’s tenure, up to the 1906 sale of his estate for subdivision, this rural village began its transformation to suburban enclave.

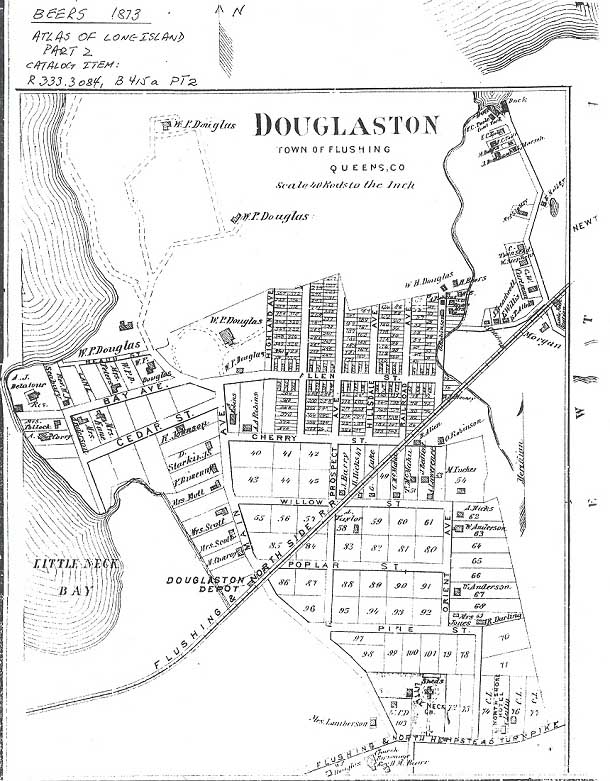

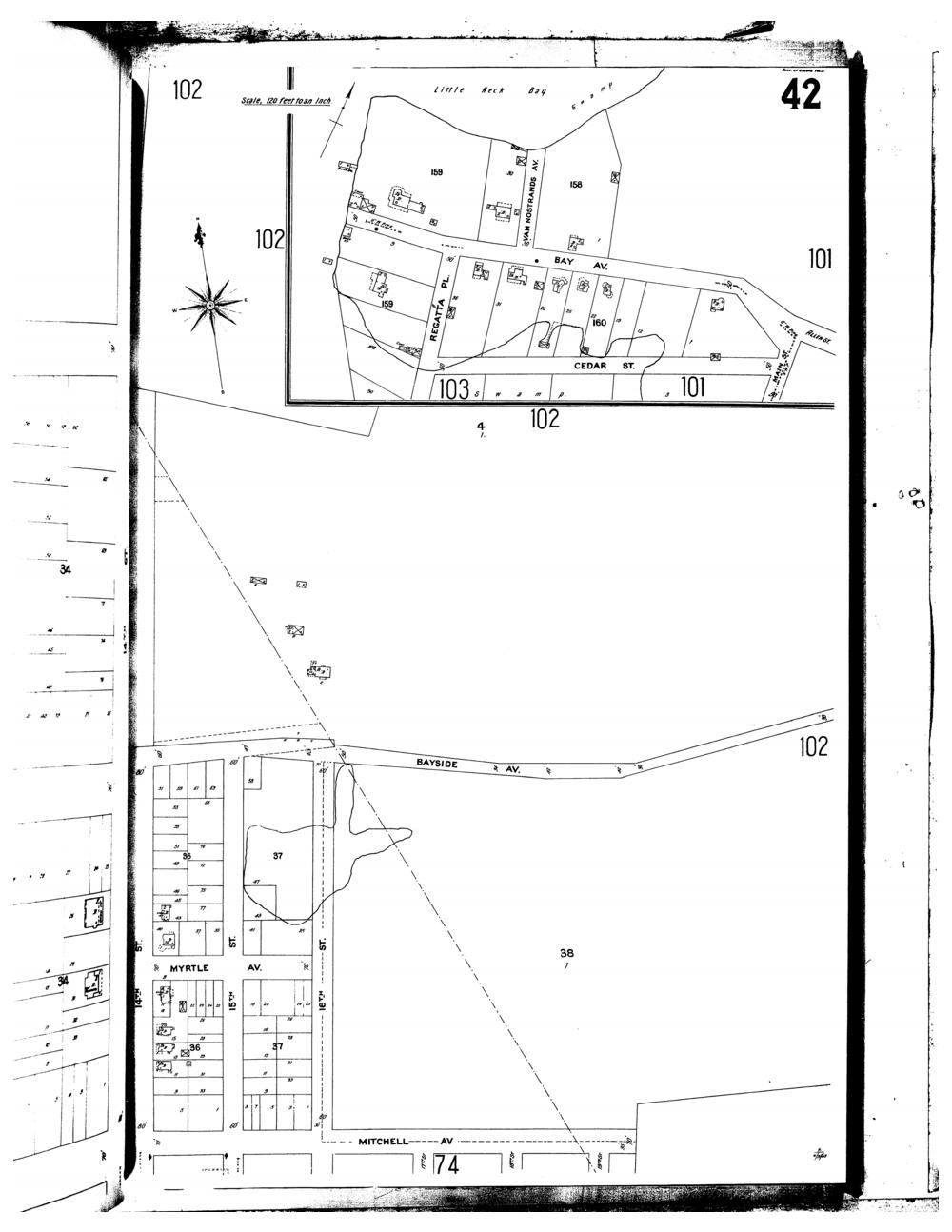

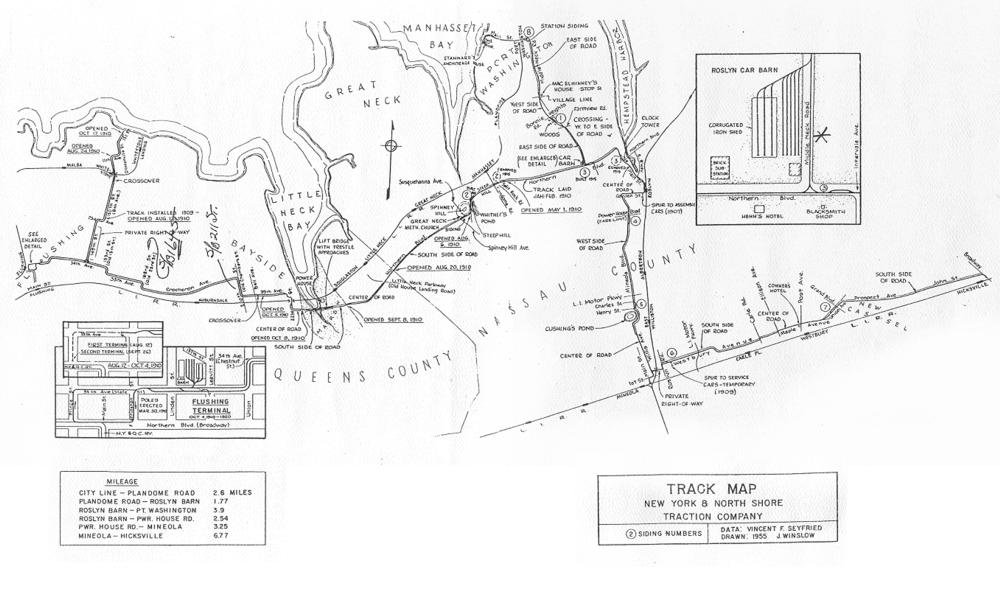

The transformation began with the subdivision and sale of the Lambertson property in 1853. While little is known of Lambertson, the nature of the sale indicates that he was likely banking on the coming railroad to ensure a successful land venture. The Flushing & Northside Railroad extended to the Village of Flushing in 1854, and as far as Great Neck, presently Nassau County, Long Island, in 1866.15

On February 15, 1853, the Flushing Journal reported that a party of 16 persons arriving by omnibus had purchased the farm of Jeremiah Lambertson, with the intent of building 16 country seats upon it. Property deed records show that title was transferred on July 23 and 27, 1853, from Lambertson to 18 buyers, with most buyers purchasing three and four lots each.16 These lots had been laid out in generous 200′ x 200′ lots, set amid a street grid within the natural boundaries of the Alley Pond and Udall’s Cove marshes. The streets were named for trees, e.g., Pine, Cherry, Poplar, Willow.17 No country seats were built however, and the land remained mostly vacant until the turn of the century.

The Suburban Development Context

Because the Douglaston Hill subdivision was one of the earliest in northeastern Queens (Woodside and Bayside, both earlier stops on the Flushing & Northside Railroad, were not laid out until 1867 and 1872 respectively) its fifty-year evolution from mapped lots to built form provides a window onto how the commuter suburb developed as a physical and psychological manifestation of American middle class values.

While Lambertson created a new locale with his subdivision, it is relatively clear that he did so as a speculator. Nevertheless, one important context for its development was the nascent movement among landscape artisans and architects to create naturalistic compositions of rural residential enclaves connected to the city by rail. The ideas of a new and distinct form of community planning had their origins in the garden city movement of England of the 1820s, wherein the characteristics of rural, domestically-centered preindustrial environments were consciously incorporated into new towns.

These ideas were becoming more widely known around the time of Lambertson’s sale.

It is widely held that their first expression in the United States was in the picturesque semi-rural cemeteries created in the 1830s. The popularity of these cemeteries with city dwellers turned them into parks and picnic grounds. Many early suburban residential projects incorporated design elements of the cemeteries, such as contrived naturalistic landscape and street names evoking natural features.18

By mid-century, a group of writers and designers had created a “cult of domesticity,” proclaiming the moral virtues of family, home ownership and semi-rural dwelling. Catherine Beecher’s widely read Treatise on Domestic Economy (1841), and Andrew Jackson Downing’s A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1841), were among the first books to offer house plans, and argue that gardens and home ownership were key to harmonious family life. Widely read, these books were instrumental in formulating the American domestic ideal.19 Consequently, they were influential in the development of the suburb, a phenomenon which architect and scholar Robert A. M. Stern has described as “…a complex embodiment of American aspirations deeply rooted in the national psyche.”20 By the 1850s, many of Downing’s principles were being expressed in the suburban developments created by his partner Calvert Vaux, architect Alexander Jackson Davis, and landscape designer Frederick Law Olmsted.

In 1853, Davis and developer Llewellyn Haskell created Llewellyn Park, New Jersey, the first American suburb. Twelve miles from Manhattan, it was a 350-acre development with a strip of common parkland, curving streets, a consistent architectural expression and a pastoral landscape. Llewellyn Park embodied the essence of what would become the characteristic suburb, but for the fact that it was several miles from a railroad station and thus impractical for all but the very wealthy.21

The creation of Riverside, Illinois — by developer E. E. Childs and designers Olmsted and Vaux in 1869 — brought the element of accessible transportation to bear on the suburban ideal. Childs’ notion that a rural retreat must be convenient and community-oriented resulted in the creation of a town center around the railroad station, establishing the basic premise of suburban enclaves. Riverside incorporated development stipulations to protect its character, especially to ensure “both the town’s appearance of affluent spaciousness and a general visual coherence by keeping landscaped areas primary.”22 These included stipulations on how a house could be sited, and a minimum lot size of 100′ x 200′.

No direct evidence links the subdivision of the Lambertson property in Queens to the emerging ideas about suburban living. Still, the development history and the physical environment in place today reflect period responses to Victorian design principles and social values — and the budding suburban ideal.

The Lambertson subdivision only slightly interrupted the existing village community’s organic growth. The Hill’s core development occurred some fifty years later, between 1900 and 1930. Douglaston Hill became a suburban enclave in form, but unlike many later suburban developments, which ensured homogeneity via restrictive covenants, Douglaston Hill maintained its mixed economic and racial composition for many years.

Community Development Context

At the time of the 1853 subdivision, Zion Church was twenty years old. The village at Alley Pond was a shipping and trading hub, its general store providing an immense variety goods “from a needle to an anchor.” And the community of oystermen (many of whom were African American) was thriving, with more than a dozen sloops and schooners operating on Little Neck Bay at the foot of Old House Landing Road (now Little Neck Parkway).23

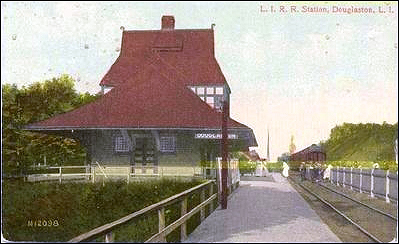

In 1867 the Flushing Railroad reached the Little Neck area, introducing an era of more rapid change. William Douglas donated a farm building from his estate to serve as the Douglaston Station; in exchange, he asked that the station and the village around it be called Douglaston.24 In 1887, Douglas and resident subscribers funded a Queen Anne-style depot building and landscaping at the new Douglaston station. Popular postmaster and gardener Albert Benz directed the landscaping project.25

The arrival of the railroad greatly reduced time to the city, but the trip still required taking a ferry from Long Island City, Queens to Manhattan. Douglaston remained relatively isolated, slowly attracting new residents. In April 1887, just prior to the Hill’s key period of growth, the Flushing Journal reported on the community’s idyllic setting: “Possessing all of the requisite features which tend to make a place of sojourn acceptable, Douglaston, indeed, is the elysium of restfulness and peace. From the old curbed wells that can be found in the yards of most of the farm houses to the stately trees that line the drives leading to the same — everything smacks of rural life in its most pleasing form.”26

Late nineteenth-century newspaper reports of activities at Zion Church and other civic affairs reveal the gradual introduction of newcomers and new ways of life into that “elysium of restfulness and peace.” The death in 1887 of Zion’s Rector Rev. Henry M. Beare marked the end of an era. Having served the parish for forty-five years, Rev. Beare was “widely known throughout the state, and in his own parish he was almost worshipped by his flock.”27 He was one of only a few Little Neck residents known beyond the immediate community. “Long Island Farmer Poet” Bloodgood Cutter, one of Little Neck’s more picturesque citizens, was another — best known as a friend and travel companion of Mark Twain’s.28 By the time of Cutter’s death in 1906, new residents — both permanent and seasonal — were introducing a more prominent, middle class commuter population into this secluded hamlet community.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, frequent reports by the Flushing newspapers record the comings and goings of seasonal residents as well as house construction for permanent newcomers. These included a bank clerk, a cigar maker, a well-known dentist (whose family resided in Douglaston for two “seasons” before purchasing property), an active suffragette, a composer of popular song, the general manager of Pittsburgh Steel interests in New York, and a prominent Manhattan physician.29

Census records from 1900, 1910 and 1920 show a range of occupational categories for Douglaston Hill — from professions such as chemist, lawyer, teacher, banker, builder, jeweler, merchant, post office and railroad stationmaster to laborers such as blacksmith, mason, shoemaker, domestic, factory worker and laundress. Several families of African American oystermen are listed in these Census records.

This community of black oystermen had existed in Little Neck, some as property owners, since the 1850s. While their homes were located outside the Lambertson subdivision (most along Orient Avenue near the dock at Old House Landing Road), they contributed to community life. Upon the death of oysterman Jacob Treadwell (1833-1904), the Flushing Daily Times reported “He was a well known character in and about Douglaston, where he has been a life long resident” This community’s church on Orient Avenue, St. Peter’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, was active for over 100 years: founded in 1872, the church building on Orient Avenue held services until the late 1980s. The Hill’s major period of development coincided with the oystermen’s decline, following the 1909 condemnation of polluted Little Neck oyster beds.30 While their numbers substantially decreased in the early years of the twentieth century, several ancestors resided in Douglaston for many more years.

The early years of the Hill’s development were led by a small group of men, whose actions as realtors, builders and home owners shaped the community both physically and socially. William J. Hamilton, Denis O’Leary, W. R. Griffiths and John Stuart were among the first to begin building within the Hill area, and they were prominent residents during the first decades of the twentieth century.

Between 1890 and 1908 six lots were developed by William and Josephine Hamilton, including their own at 240-35 43rd Avenue (Block 8106/Lot 69). Their undertaking began at the turn of the century, when they bought and sold two of the Hill’s original 200′ x 200′ lots (which had been held by only two owners since 1853). By 1908 William J. Hamilton was recorded as owner and architect/builder for four houses, and was recorded as owner of two others. In his brother’s obituary in 1907, Hamilton was described as the “well-known builder of Douglaston.”31

Like Hamilton, John Stuart was the architect/builder of record for at least three houses during the Hill’s early years, and his building plans were noted in the local newspapers.32 Both Hamilton and Stuart are memorialized by street names in the neighborhood — Stuart Lane and Hamilton Place, and Stuart’s descendants have been active builders/developers into the present day, including current renovation projects currently underway in the Hill.

In 1898 and 1901 Mrs. William J. Hamilton sold two adjacent 200′ x 200′ lots (numbers 94 and 89, respectively) to Mrs. Denis O’Leary.33 The O’Leary’s ultimately shared Lot 94 with the Hamiltons — nearly identical houses were built in 1901 on the equally divided lot. The O’Leary’s subdivided and developed Lot 89, building four houses on four 50′ x 200′ lots in 1903. Denis and Eleanor O’Leary lived in Douglaston Hill from c. 1901 to c. 1943 (Denis O’Leary died in 1943). Their two daughters remained in Douglaston Hill through the 1950s, living in separate houses across 43rd Avenue from their childhood home.

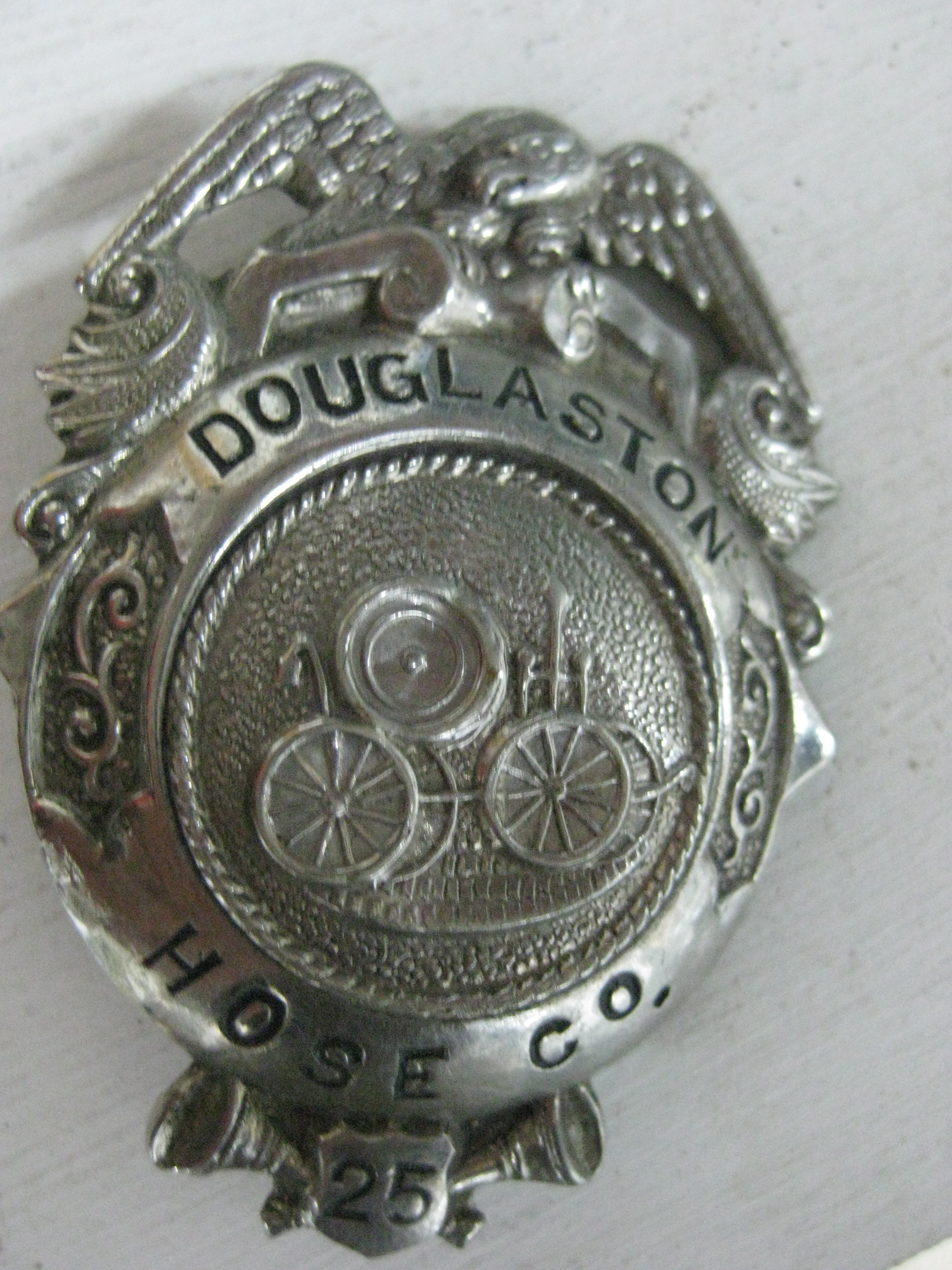

Denis O’Leary was typical of an early suburban commuter. A prominent attorney and politician, he was active in civic affairs within and outside Douglaston Hill. He served as Assistant Corporation Counsel for New York City, Public Works Commissioner, Queens County District Attorney and U.S. Congressman. Locally, he was a founding officer of the Douglaston Hose Company No. 1, officiating at many of its social functions at Zion Parish Hall, sometimes in the company of New York City Mayor Jimmy Walker. And he was active in numerous charitable and fraternal organizations, including the Shinnecock Democratic Club of Flushing (President), the Flushing Council (President), the Catholic Benevolent Legion, and Holy Name Society of Sacred Heart Church, among others. (Denis O’Leary may have been part of the founding meetings of St. Anastasia Roman Catholic Church, at the home of Otillie and Adolph Helmus at 240-16 43rd Avenue (then Pine Street) in 1915. Masses, baptisms and church meetings were held in this home while the congregation was being officially formed.)

Similarly, attorney W. R. Griffiths was typical of the new resident. Frequently cited by the newspapers as the attorney for real estate transactions within the Douglaston Hill district, Griffiths was committed to civic affairs in and beyond Douglaston. He was an officer of local Republican clubs, such as the Roosevelt & Fairbanks Campaign Club, and devoted many years to the public works of the United Civic Associations of the Borough of Queens. He was a vestryman at Zion, and led several community improvements such as maintenance of the salt meadows and ornamental tree plantings near the train station.34

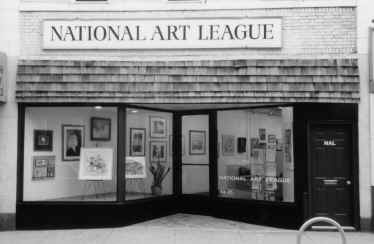

The development of a community connected to the city at large is also illustrated in the founding and continuity of the Douglaston Art League in 1930, and still active today (now known as the National Art League, located at 44-21 Douglaston Parkway). The League was founded by Mrs. Arthur Sullivan and Miss Helen Chase – sisters and daughters of New York painter William Merritt Chase – along with other residents and north shore artists who were “interested in arousing amore general appreciation of art in the community and in providing a means for practical development of individual talents.”35 Architect Aubrey Grantham (Zion Episcopal Church) was among the founders. The League’s early exhibits and classes were held in the backroom of a beauty shop and its second show was exhibited in the Parish Hall of Zion Church.

The period from 1900 to 1930 was one of enormous growth for the borough of Queens, and for Douglaston. Writing in 1936, Zion’s Rev. Lester Leake Riley remarked on the results of that growth: “By 1910 the old farms are disappearing, the old landmarks fade away, or are hidden behind these Tudor makeshift fronts, the mart of our busy shops and stores. By 1920 our village assumes an air of suburban dignity.”36 Approximately 2,000 people lived in Douglaston-Little Neck in 1920. Just ten years later the area’s population was 8,000, and Douglaston Hill was fully developed.37

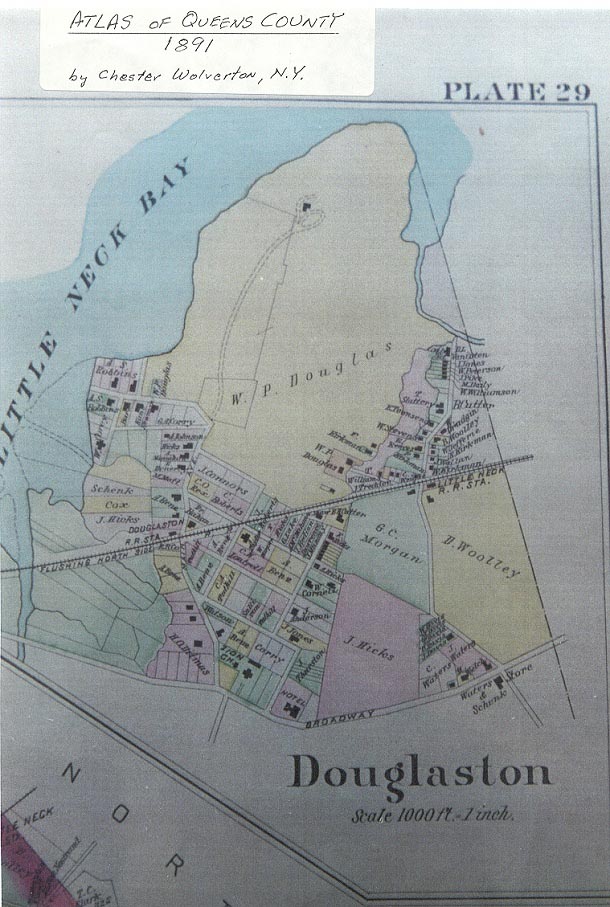

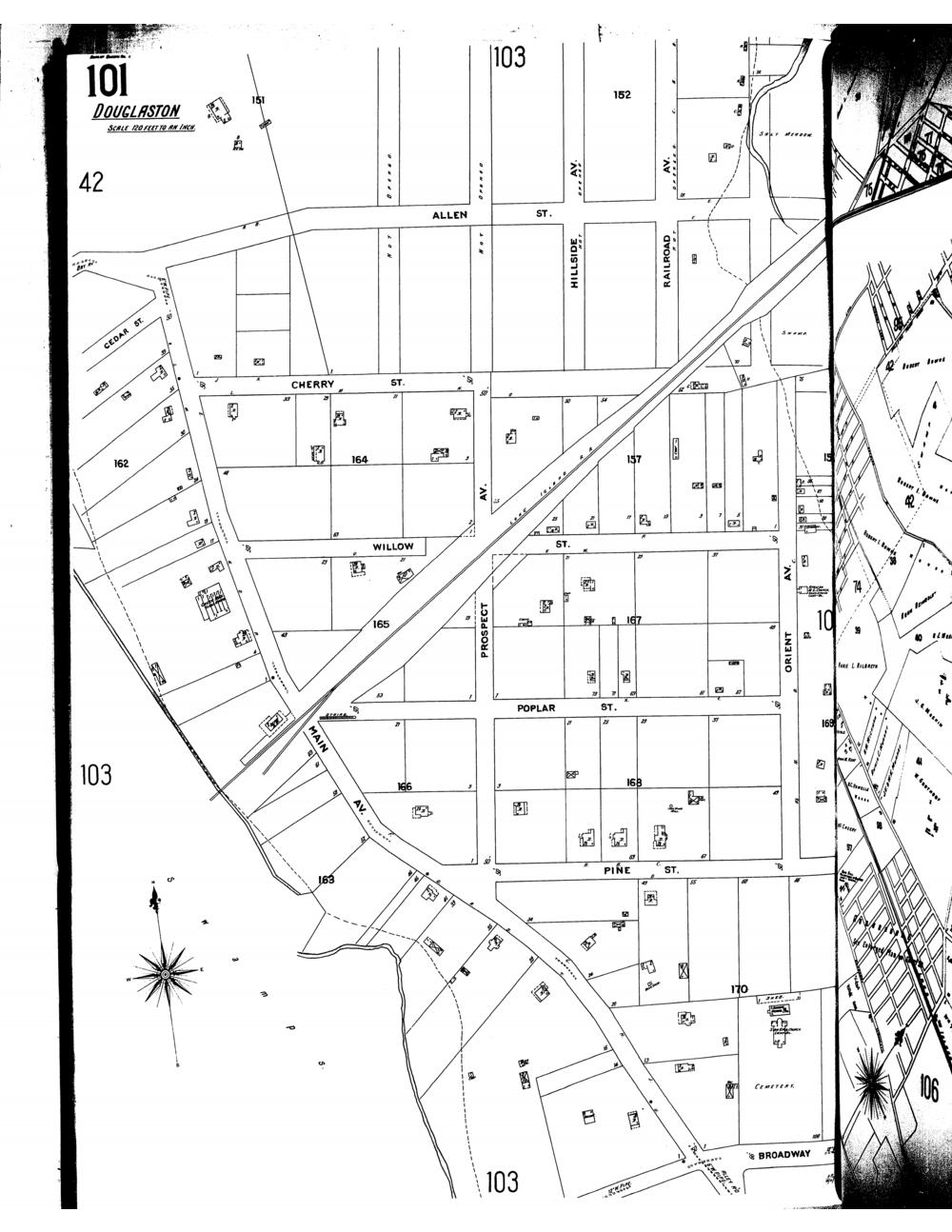

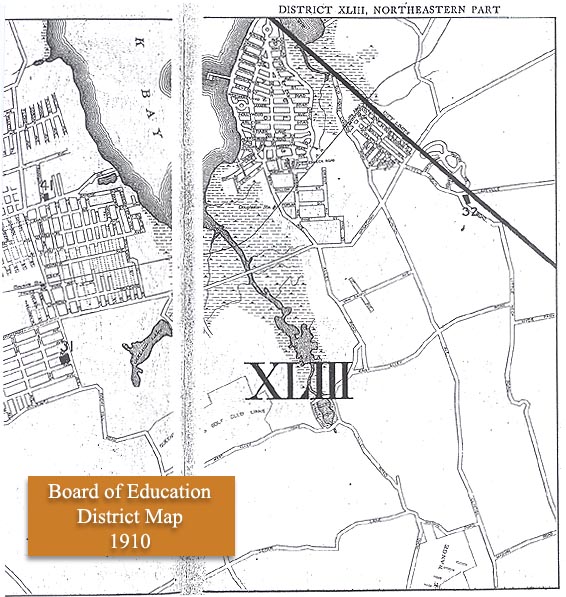

Maps

A collection of photographs from around the neighborhood

taken in early spring 2001

Neighborhood Highlights

Zion Church

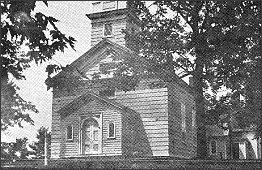

Original Zion Church

The above picture shows how the original Zion Episcopal Church, Parish of Little Neck, looked before it was destroyed by fire on Christmas Eve of 1924. The church, built in 1830, was erected at the instigation of Wynant Van Zandt, who donated the property and funds for the building. The project was a community affair, since many of the residents contributed time and materials for the building. The edifice was constructed of wood from trees cut on the Van Zandt estate. A sawmill was brought to the scene to prepare the lumber and everybody helped with the work. The original church had no middle aisle and the pews were made of pine. Dedication ceremonies were held on June 17, 1830.

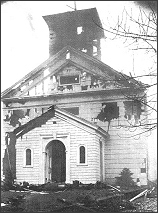

Zion Episcopal Church

“Shortly after the disastrous fire of 1924, the church was rebuilt, using a modern design. More rooms were added and the church itself was somewhat larger. The new church was ready for formal opening on December 25, 1925. In 1929, fire broke out again and destroyed the chancel, sacristy and the choir rooms. When rebuilt, the sacristy was enlarged to provide a study for the rector. The White Church on the Hill — as it was called — is shown above. A portion of the newer section of the churchyard may be seen in the foreground. The original graveyard area is west of the church buildings.”

“Shortly after the disastrous fire of 1924, the church was rebuilt, using a modern design. More rooms were added and the church itself was somewhat larger. The new church was ready for formal opening on December 25, 1925. In 1929, fire broke out again and destroyed the chancel, sacristy and the choir rooms. When rebuilt, the sacristy was enlarged to provide a study for the rector. The White Church on the Hill — as it was called — is shown above. A portion of the newer section of the churchyard may be seen in the foreground. The original graveyard area is west of the church buildings.”

Detailed History

(From a booklet published by Zion Church)

In the year 1813, the land on which Zion Church is situated – and the surrounding area – was in the possession of the Van Wyck family. This year saw one of the last mail deliveries by stagecoach at the Little Neck Post Office at Alley Pond, and that year Wyant Van Zandt, as prosperous city merchant and alderman, acquired 120 acres along the shores of Little Neck Bay and settled down to the life of a farmer with his sons to help him. The family lived in the old Colonial house on West Drive, Douglaston, now owned by the Larson family. Here they lived until 1819 when the “mansion” now occupied by the Douglaston Club supplanted the Van Wyck house and became the Manor house of the old farm. Mistress Van Zandt was the mother of seven sons and four daughters, and the new house with its big square rooms must have been none too large.

Wyant Van Zandt and his wife Maria were good neighbors in this community, gaining the friendship of other farmers who cooperated with him in breaking through the meadow which now crosses Northern Boulevard, saving the long way around Alley Pond and shortening market trips to the city. Much later, in the process of widening and straightening the Boulevard, previously called Broadway, the site of the Matinicoc Indians’ last battle and the graves of the slain were cut into, and the Indian remains were transferred to Zion Churchyard.

Wyant Van Zandt and his wife Maria were good neighbors in this community, gaining the friendship of other farmers who cooperated with him in breaking through the meadow which now crosses Northern Boulevard, saving the long way around Alley Pond and shortening market trips to the city. Much later, in the process of widening and straightening the Boulevard, previously called Broadway, the site of the Matinicoc Indians’ last battle and the graves of the slain were cut into, and the Indian remains were transferred to Zion Churchyard.

The Van Zandt family were faithful in their religious duties and drove to Christ Church, Cow Neck, Manhasset, where Wyant Van Zandt was a communicant, to attend the services conducted by the Reverend Eli Wheeler, brother of Maria. Wyant Van Zandt also established regular Sunday worship in the East parlor of his home and later built an octagonal structure with two wings to serve as a chapel.

A Church for Little Neck

When, after a few years, Mr. Wheeler took the rectorship of a church in Shrewsbury, New Jersey, Mr. Van Zandt broached the subject of a church for Little Neck, as this community was then called. Finally, he decided with the help of his neighbors to build the church himself. So his chief gift to this community was the donation of land and funds for the building of Zion Episcopal Church and Sunday School. All of the following signed a “document” pledging funds for the building: Wyant Van Zandt, Roe Haviland, Philip Allen, Eliza Allen, Richard Allen, Jeffrey Hicks, Joseph L. Hewlett, Jerome Van Nostrand, William Haviland, Thomas Hicks, Henry S. Cornell, Charles Peters, Richard Place, Thomas Foster, Jeremiah Valentine, Robert Van Zandt, Edward Van Zandt, and Washington Van Zandt.

The New York architect Upjohn furnished the plans; Stephen Cornell was the builder, and Will Buhrman of Alley Road, the painter. All of the materials which went into its construction, except the glass for the windows, came from local sources. What the people could not give in cash they gave in labor and materials. The smith at the Alley hammered out the hand-wrought hardware and nails; Van Zandt and his neighbors cut their finest trees for beams and rafters, and a sawmill was brought to the scene to prepare the lumber. Even the boys were allowed the task of making the shingles for the bell tower.

At a great neighborhood raising the cornerstone was laid in 1829. The building was completed and opened for worship according to the usages of the Protestant Episcopal Church on June 17, 1830. Records recounting the raising of the church and its dedication include the names of nearly every family in the vicinity and the supper table set out on the grounds to celebrate its completion stretched half a block down the road.

Consecration

Bishop William Henry Hobert of the Protestant Episcopal Church of New York formally consecrated the brown church with the square tower and the cemetery on July 30, 1830. And they called it Zion, the Hebrew word “Tsiyon” meaning hill, also “Heavenly.” Perhaps they were thinking of Psalm 48 “Beautiful for situation is mount Zion” and certainly so were the church and its grounds.

First Rector

The Reverend Eli Wheeler was brought to Zion Church as its first rector and he served until 1837. A description of the congregation from an observer of the time follows: “I looked over the congregation and observed them carefully as I came with them out of the house at the close of the service, and saw that they were rural and simple folk; not rude, but unfamiliar with what is called the world; and under the wise teachings of their noble pastor and preacher they were being trained intelligently for the true enjoyment of religion and for the glory beyond the skies. Happy people!”

The original church building had neither chancel nor middle aisle. The elevated pulpit stood against the wall before the people, and below it on the ground floor, surrounded by a railing, was the plain “Communion Table” or Holy Table as it is called in the Prayer Book. It was the custom of the minister to wear the old-fashioned full-flowing surplice over his clothes together with a black stole, which he would change just before the sermon and appear in the pulpit gowned in a black robe with white hands at his collar front.

Wyant Van Zandt died in 1831 at the age of 64. His body was interred in the family vault beneath the church, its only monument being the marble tablet to his memory upon the church wall above the vault. Six other adults and four children were also interred in the vault. The Parish has records on each, and their remains were lowered below the new floor during the 1965 consecration.

Although Henry Van Zandt continued to live on a part of the farm after the death of his father, the major portion of the land was purchased in 1835 by George Douglass, “a Scot of quiet tastes and great wealth,” and its name changed to that of the newcomer, “Point Douglass.” The Douglass family were active members of Zion Church and contributed the chancel of the church, stained glass windows, and an organ in 1863-64.

In 1842, the Reverend Henry Marvin Beare came to Zion Church as its Rector. He was loved and respected not only by his parishioners, but also by all the community. An incident of embarrassment during his tenure was his discovery that the coachman, after driving the rector on his parish visits, had returned at night to these homes and robbed them of their silver and other valuables. The coachman hid the stolen goods in the belfry of the church, where the Reverend Beare discovered them quite by accident. The shock to him was very great, though naturally no one held the rector or the church responsible for the thefts. Dr. Beare’s teaching was always based on the Book of Common Prayer and it is said that he distributed hundreds of copies of it as gifts.

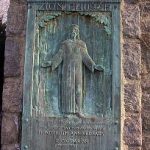

Henry Bear died January 9, 1887, ending forty-five years of loving and faithful service to his parish and the community. The bronze tablet on the east wall of the church, presented in January of 1894 as the gift of the people, is to his memory.

Several rectors followed the Reverend Beare, and in 1902 the Reverend Albert Bentley came to Zion. His wife, Nellie, was organist and choir director. Many choir concerts, Gilbert and Sullivan operettas, and other plays were given under the direction of Mrs. Bentley.

Parish House

On October 3, 1896, the cornerstone was laid for the Parish House. The building was dedicated on May 23, 1897, and became the social center of the parish and the entire community. Bowling alleys had been built in the basement, monthly socials were held as well as annual fairs, strawberry festivals, church suppers, and other events. The rector, wardens, and vestry permitted outside organizations to use the Parish House free of charge, and there was always some kind of activity, even as there is today.

Since the neighborhood of Little Neck was growing fast, it was decided to call the new station “Douglaston.” So, as part of Douglaston, Zion stood, in the simple design of a country wayside church with its square bell tower, for a period of 94 years.

1924 Fire and Re-Building

An outstanding event at Zion was the Children’s Christmas Festival. In the year 1924 the children were all safely home and tucked in their beds after such an occasion when fire broke out in the old building. Every effort was made to check the flames, but they had made such devastating headway before the fire was discovered that is was of no avail.

The rector at the time was the Reverend Robert Black. Through the courageous efforts of Dr. Black and his wife, items of great historical value, the cross, the communion set, collection plates and candlesticks were rescued. The altar cloths and drapes were lost and the organ was ruined; the bell which had sounded for four generations fell from the blazing belfry and burst into fragments. The interior of the Parish House, recently rehabilitated, became a shambles.

The burning of Zion Church shocked the entire community. Expressions of sympathy came from all sides and promises of support from near and far without regard to creed or denomination. Community Church threw open its doors and its pastor, the Reverend Eugene Flipse, placed every facility at the service of Zion. The Christmas Holy Communion Service was held in the new Community Church building.

Steps were taken at once to rebuild, and Dr. Black called a meeting at which Aubrey G. Grantham was present. As originally built, the church was slightly short for its breadth. A longer nave, barrell-vaulted ceiling, and the possibility of a spire were debated. Mr. Grantham became the sole architect and the result was a dignified, restrained and scholarly performance, a restoration made perfect with additions which are part of the proper design of the Colonial period. The Architectural Record of March, 1927, showed the church as an illustration of simplicity and restraint in design.

The Parish House, rebuilt at the same time, was kept to the Colonial design and shares the dignity and simplicity of the church. The auditorium sets 150 persons, and is provided with stage equipment for theatricals. There was a good kitchen, and at the time the downstairs included a Guild Room and Boys Club Room. The builder was Samuel Lindbloom, also of the parish.

The following is a description of the church, open and ready for worship on Christmas, 1925: “The old floor and beams remained at the time of the rebuilding, except for the area destroyed by the crash of the bell; and of course the bell was rebuilt. The Colonial interior of the church has beauty of its own. No “dim” religious atmosphere was intended. Daylight pours through the open panes of glass, tinged here and there with a lavender hue. The sixteen-over-sixteen windows are beautifully proportioned, and the church is bright and full of quiet dignity and cheer. The pews are Colonial design, and comfortable.

“The altar rail encloses the completed apse, and the rounding curve of the wall is pierced at the top by three clear glass circular windows. Before the middle window rises a white cross that surrounds a frame of simple design serving as the reredos for the altar, and into its frame is a rich damask cloth of red and gold. With this lovely background the re-table of the altar supports on either side the ornate brass cross, the two eucharistic candlesticks and the flower vases. Just beneath, emblazoned in gold, are the words COME UNTO ME.

“The altar is in keeping with the church and offers no ornament but a white painted wood-carved medallion on its front of the pelican feeding her life’s blood to her brood, and symbolizes our Lord feeding the faithful with the Blessed Sacrament.

“On one side of the Sanctuary is the Bishop’s Chair; opposite, the clergy chair. The choir stalls are arranged in the chancel, and the organ chamber is to one side of the choir. The Baptismal Font is to the front of the chancel. The Lectern, or reading desk, which supports the Holy Bible, is wrought in brass in the form of the conventional eagle. The pulpit is of brass and wood, and beside the pulpit stands the flag, symbol of the Soul of America. Simple Colonial candelabra serve for the electrically-lit chandeliers.”

Fire broke out again in 1929 and destroyed the chancel, sacristy and the choir rooms. In rebuilding, the sacristy was enlarged to provide a study for the rector.

Several years later an attempt was made to introduce into the church pseudo-Gothic or Medieval features which would have required a complete alteration of the existing structure. A majority of the parishioners felt this would produce a synthetic atmosphere of ritual, foreign in thought and infinitely removed from the faith and spirit of the original founders. Strong protest blocked such a move and the simple dignity of the Protestant Episcopal Parish Church endures.

Later additions to the church include the bronze plaque at the church gate, inscribed “Out of the Woods My Master Came,” which was a feature of the centennial celebration in June, 1930. The carving on the same theme, inset behind the altar, is believed to have been created by the Norwegian sculptor, Tryglive Hammer. The frontal of Coronation Tapestry was given to the church by the Altar Guild at the time the altar step was removed.

The three clear glass circular windows have been replaced by stained glass as a memorial to Mrs. Theresa Gabler, and were installed during the tenure of the Reverend Marland W. Zimmerman, who served as rector from 1944-48.

The Credence Table at the east of the Altar supports the silver cruets, a gift of the Woman’s Guild, and there is another flag now to the west of the Chancel, the Church Flag, the red cross on a white field being the oldest Christian symbol.

At the south end of the church the balcony front was altered in 1959 to accommodate a new Moeller organ. This fine instrument was given as a memorial to Elizabeth Vanston Morgan, long-time resident of Douglaston and a member of the Altar Guild. The choir stalls were moved from the Chancel to the balcony at this time, happily yielding an unobstructed view of the curved sweep of the chancel wall and altar.

In the vestibule of the church is a tablet inscribed with the names of several parishioners who, in 1950, gave the tower bells now in use.

In the unusual winter of 1994 handicap access to the church was achieved by installing a three-station elevator on the east side of the building; entry is a ground-level vestibule, with stops on the main floor and in the undercroft. During construction of the lift it was discovered that a new flue was needed in the chimney and near-record snows of that year created problems for workers and parishioners. Later in the spring the altar was brought closer to the congregation by removing one step in the chancel and moving the altar rail to pew-level.

Undercroft

On September 11, 1964, during of the Reverend Canon Everett J. Downes; an ambitious program for the preservation and expansion of our facilities was started. It was found necessary to replace some of the old timbers found under the church, left from the original 1830 building, and it was decided to dig out under the present church and put in a full basement.

The Parish Co-chairmen of the project were William H. Borst and William H. Williamson, Jr.; the architect was Guercino Salerni of Long Island City, and the builder was W. Frank Wilkinson of College Point. The ten new rooms with space for classrooms, choir practice, robing accommodations for the choirs and acolytes, and a spacious library, are ‘bright and commodious, and can be reached from either the back or front of the church by stairways. New furniture was provided for the rooms as gifts or memorials from parishioners. The office on the first floor was greatly enlarged at this time.

Rectory

Before the present rectory was built, Dr. Beare occupied a residence which stood on the south side of Northern Boulevard and was given to the rector, rent-free, by Mr. William F. Douglass, and, no doubt, his father. At a meeting of the Vestry on April 23, 1989, the rector reported that the late George Hewlett had in his will bequeathed $1,000 to the church, the interest to be given annually to the rector, or, in the event that a parsonage was to be built, the entire amount to be appropriated to that project.

In 1889 the Minister-in-Charge, the young Reverend William S. Barrows, inaugurated the campaign for building the Beare Memorial Rectory on the two-and-one-half acres of land facing Douglaston Parkway, purchased for $250 one hundred years ago. A second $1,000 was given by the Hon. John A. King and about $2,000 from the congregation, so that forty-one years after buying the land for that purpose sufficient money was at last on hand to build, and the rectory was completed in 1890. Edgar Lewis Sanford was the first rector to occupy it. The name of the man in whose memory it was built was intended to be inscribed on the stained-glass shield at the landing of the stairs to the second floor. The sexton’s cottage, later removed, was built in 1861 on part of the ground adjoining the churchyard.

Churchyard

An acre of land to the east and west of the church was added in 1834 by a gift from Joseph de Forest, and was to be used as a cemetery. In 1885 Bloodgood H. Cutter deeded an additional two acres to the east of the church in memory of his wife. Burial plots were first laid out on the west side and here can be found the names of most of the original “document” contributors. The whole of the grounds now comprised nearly seven acres.

In 1957 a city block across from the rear of the Parish House was purchased, and an acre and a half of asphalt-paved land now serves

as a parking lot.

The Churchyard is on high ground and has no atmosphere of death and corruption which characterizes an old neglected spot. The grounds are attended and the “winds of heaven” blow through the trees.

A memorial to the Matinicoc Indians was dedicated on Sunday, November 1,1931 marking the closure of their ancestral burial grounds on Northern Boulevard and Jesse Court in Little Neck. The site of the re interring is marked with a tribal symbol, a tree growing from a split rock.

Surely in these cemetery grounds can be felt the spirit of our well-known hymn,

The mystic sweet communion

With those whose rest is won.

In the Easter, 1973, Zion monthly Bulletin, a piece entitled “A Churchyard Stroll” appeared from which the following is quoted: “Helen Drewes, landscape architect and the Douglaston Garden Club’s tree expert has listed Zion’s outstanding trees:

“West of the driveway, yellowwoods, a ginko, large old Japanese maples, and a cultivated sweet cherry which is the largest in the vicinity and was obviously planted by early settlers.

“East of the circling driveway, a white ash, identifiable by diamond-shaped markings of the bark; another white ash but in poor condition on the west side of the driveway; a Chinese elm southeast of the main entrance, its small thumb-sized leaves giving it a feathery effect; several black locusts set back from and along the main drive.

“Along the ‘within-cemetery’ driveway, on the left before the bend, a hackberry tree, sometimes known as witch’s broom; Sophora, or pagoda tree – when older it has sweet smelling white blossoms wisteria-like in shape. On the right, after the bend, two Kentucky coffee trees, specimens and very old. Their name is derived from the fact that early Kentucky pioneers used the beans in place of unprocurable coffee.

“Among trees planted as memorials in recent years, enhancing the pleasing prospects of a Churchyard stroll, are a Japanese maple at Lawrence Harvey’s grave, a red hawthorn given by the Garden Club in loving memory of Edith King, and a pink dogwood to scatter its petals over eleven-year old David Scanlan, which not long afterwards sheltered his mother and father as well�”

A dogwood was placed near the Northern Boulevard wall and west of the driveway in 1989 by the Douglaston Garden Club in memory of Catharine Turner Richardson.

Churchyard Tour

In 1995 a tour of the churchyard was developed beginning at the large stone “Cutter” cross just west of the building. Here are the weathered markers of families who buried loved ones following the 1830 dedication: Haviland, Allen, Cornell, Hicks, Lawrence. Just south of here is a stone marked “Mary Buhrman.” Between the stone and the white barn is the grave of Benjamin Lowerre. He purchased a general store and grist mill from the descendants of the Foster family, who had settled Allen Creek in 1637. Mary Lowerre married William C. Buhrman, whose name was associated with the store and mill in later years. The Alley was important because, before the road crossing the Creek and later named Northern Boulevard was built, the only route east and west went through the Alley just south of Alley Pond.

Between the “Caroline Bissell” cross and the barn is the Edwin Lawrence stone. This family owned burial plots on the east and west sides of the early churchyard, and they owned the section that was later developed as Marathon Park.

Farther south are several plots marked by low railings: the first belongs to Albert S. Griffin, an early Douglaston resident who traveled abroad and has been credited with importing seedlings of a variety of exotic trees such as the weeping beach at the Douglaston train station. John Bennem and his son Charles were for many years the Little Neck village blacksmiths who operated a shop on Little Neck Parkway just south of where the Chase Bank now stands. The next plot is Henry Benjamin Cornell, a life-long member of Zion. The last railed plot is the Schenk-Hicks families. Benjamin Schenk was a partner of Schenk and Van Nostrand, who operated the General Store in a white wooden frame building on the current site of the Chase bank. Mrs. Schenk’s father, John Hicks, owned several farms in the area between where the Long Island Expressway and the Grand Central Parkway currently lie.

Across the driveway and south of the “Cornell” bench is the plot of Alfred P. Wright, a wheelwright in Little Neck. The plot also contains a poignant stone for a daughter who died at the age of twelve, as well as an unusual cast-iron grave marker.

Closer to Northern Boulevard is the Hutton family plot, featuring another Victorian cast-iron marker. Behind the “Cornell” bench is one of the Hicks family plots.

The large “Bryce Rea” stone near Northern Boulevard is part of a more recently developed section containing the family plots of many local merchants: John Gabler, Bryce Rea, Doyle Shaffer, and others. From here on a clear day the towers of lower Manhattan can be seen to the west.

In the midst of a grove of cedars is the marker for John Gibson who served as Sexton for Zion Church for many years. To the left is the marker of Charles Hallberg, who along with Donald Kirkpatrick moved their families to Douglaston when Queens College was founded in 1938. They were two of the original twenty-eight professors of the college. The Kirkpatrick stone lies flush with the ground near the tall pine tree.

The Matinecoc graves, to the north near 44th Avenue, are described elsewhere.

Toward the church from here is the “Mott” marker. This is the second oldest portion of the churchyard. Members of the Mott family lived in Douglaston since before the Revolutionary War. To the left is a marker for the Van Nostrand family, also long-time residents of the area.

Memorial Fund

The Memorial Fund was created in 1965 to give scope and direction for gifts to the church. There have been many gifts over the years, and, in addition to those mentioned in earlier parts of this history, are the following:

The Litany Desk (prie-dieu), designed in appropriate Colonial style by Aubry Granthan, was presented to Zion Parish by Mr. and Mrs. William Allen. When litanies are said, the desk is placed at the head of the aisle, to signify that prayer and the leading of prayer are rights of the people. The rector comes down among the congregation and prays with them.

The Altar has a plaque affixed to it which reads: “This Altar, set apart to God’s honor and Worship at the solemn consecration of Zion Church, December 25, 1925. The loving gift of Mary Helmus.”

The pulpit was given by Mrs. Mary Helmus in memory of her husband, Adolph, who died in November, 1920. The chalice and paten now in use were given anonymously in Lent, 1946.

A chair, used by the Bishop when visiting the church, was given as a memorial to Mary Edith King by the Woman’s Guild in 1970.

In 1972 Richard Jundt hand-fashioned a four and one-half foot high cross from a railroad tie: he sanded it to a fine finish and applied many coats of white lacquer. The aumbry, or tabernacle, was given in the same year as an altar centerpiece by Marie and Charles Tuttle in memory of Mrs. Tuttle’s parents, August H. and Emma N. Former.

In 1973 the Jacobean tapestry front, called a “carpet of silk,” was donated by the Altar Guild. The chancel furniture was given in May of 1977 as a memorial to Canon Everett Downes. In 1978 an oriental prayer rug was given for use in front of the altar, again by Marie and Charles Tuttle in memory of Mrs. Tuttle’s parents. Mabel Carlander of Deer Isle, Maine, hand-hooked the rug, choosing the pattern and colors to harmonize with the church carpeting. Helen and Marion Gunning added the fringe.

The Vestry purchased a thirteen-ounce gold-lined chalice for festive occasions, using the Sorenson Memorial Funds as the family requested, in December, 1975, in memory of Charles M. Sorenson.

White Eucharistic vestments for use at the great festivals in the Church Year were given to the Parish in October, 1975. The Chasuble is the gift of the Altar Guild, and the Dalmatic and Tunicle for the sacred ministers is the gift of Mrs. Donald Fenn in loving memory of her husband.

St. Catherine’s Guild secured, in October, 1975, as a memorial to members Mrs. Louise Fasick and Miss Rose Stokes, a Coat of Arms of the Diocese in gilt and full heraldic colors by the artist Robert Robbins. The piece is installed on the choir gallery wall, and is also the gift of family and friends.

The symbol of the Risen Christ once affixed to a white cross above the altar was a memorial given by the Reverend Douglas A. Campbell on Easter Sunday, 1975, for his grandparents.

The church railings were given by Dorothy Cobleigh in 1988 in memory of here mother, Nell Gressitt Cobb. The 1982 Hymnals were given in 1986 by Marguerite Kirkpatrick as a memorial to her husband Donald Kirkpatrick.

The churchyard illumination and restoration of the lamps at the foot of the driveway were given in 1988 by the Vestry as a memorial for Antoinette (Toni) Hicks, longtime parishioner and devoted Douglaston resident.

On June 16, 1991, a white funeral pall was dedicated by Canon Cayless; the pall, with the Coronation Pattern design, and a lining of gold satin was given by the Zion Church Altar Guild and was partially funded by memorials for the Reverend Rex Burrell, rector of Zion Church 1970-86.

In 1996, the fence along Douglaston Parkway was improved and a garden at the corner of 44th Avenue was created in memory of Emil Brock.

Early Parishioners

A few words about some of the early workers for Zion. Mr. Henry S. Cornell, one of the eighteen signers of the document of 1829, had a large family. His sons, Archibald, Benjamin, and Henry all served as vestrymen. His son Augustine was the first young man from Zion to enter the ministry. His first church was the Episcopal Church in Nyack, New York, where he remained rector until his death at the age of seventy-four. This branch of the Cornell family has been active in Zion since 1830 and was represented by Alice Huestis, Clara Allen, Edna Randel Schulz, and Ruth Allen.

When Benjamin P. Allen died, Bloodgood Cutter, “The Farmer Post of Long Island,” wrote:

No more at church on Sunday meet,

No more will we each other greet,

Vestry meetings he’ll no more attend,

No more meet as friend to friend.

Mr. Cutter served on the Vestry for many years. At his death, most of his extensive library was given to Zion, including many books by Mark Twain. Cutter and Twain had traveled together extensively, and it is one of their trips to the Orient that prompted the writing of “Innocents Abroad.” Unhappily, this library was destroyed in the fire of 1924.

Dr. Edward Trudeau was a Vestryman for two years and was married to the Reverend Beare’s daughter Charlotte. He became ill of tuberculosis in 1872 and moved to the Adirondacks to dies in a place he loved. Surprised to find his health greatly improved after the first winter, he decided to stay on, making Saranac Lake his home for the forty remaining years of his life. He built Trudeau Sanitorium for the treatment of tuberculosis, and out of his own experience developed a method of treatment which was to have wide influence in the arresting of that disease.

Robert Louis Stevenson spent the years 1887-1888 at Saranac Lake as a patient of Dr. Trudeau and wrote some of his finest essays there. The Trudeau School of Tuberculosis grew out of the Saranac Laboratory and the memorial Foundation established after Dr. Trudeau’s death.

Mr. William Buhrman ran the general store at Alley Pond in 1828. The store served the neighborhood for nearly a hundred years, and it was in this store that the first Post Office of Flushing Township was established. Mail was brought by stagecoach, post rider, and boat. Mr. Buhrman and his son William gave generously to Zion.

Lewis Cornell from Little Neck, the only Revolutionary soldier buried at Zion, joined the militia and served under Colonel Humphrey in the Fifth Regiment of Dutchess County. He returned home to become active in civic affairs, and in 1798 was chairman of the Town Meeting in Flushing which petitioned the repeal of the Alien and Sedition Acts. He died in 1836 and was buried in the Cornell homestead cemetery. When Horace Harding Boulevard was widened all the remains from this cemetery were interred at Zion.

Civil War veterans buried at Zion are C. A. Bissel, William Pudney, W. H. Doremmus, W. H. Brower, John Cutter, W. Thurston, W. E. Cornell, John Starkins, Albert Griffin, Theodore Lambertson, Joseph Starkins, Horace Leek, William Corey, and John King.

The Zion Centennial Ode, music by long-time organist, Lyra Nicholas, and words by Reverend Lester Leake Riley, closes this history:

Our grateful memory and praise

Upon those villager of yore

Who drove their dust trailed wagon ways

Before its ever-welcome door.

Beneath the grass and trees they rest

While flowers flecked with dew and sun

Mark this dear spot they loved the best

Now their brief day of life is done.

Rectors Who Have Served Zion Church

- The Rev. Eli Wheeler (1830-1837)

- 1837-1842 (no Rector)

- The Rev. Henry Beare (1842, Minister in charge; 1845-1887, Rector)

- The Rev. William Stanley Barrows (1888-1890)

- The Rev. Edgar L. Sanford (1890-1892)

- The Rev. Charles N. F. Jeffrey (1892-1898)

- Dr. John B. Blanchet (1898-1901)

- The Rev. Robert M. W. Black (1901-1902)

- The Rev. Robert Bentley (1902-1917)

- The Rev. Robert Black (1918-1928)

- Dr. Lester L. Riley (1928-1942)

- Dr. Henry Santorio (1943, Locum,. Tenes)

- The Rev. Marland Zimmerman (1943-1948)

- Canon Everett J. Downes (1948-1969)

- The Rev. Rex Littledale Burrell (1970-1986)

- Canon Phillip L. Lewis (1987, Interim Priest-In-Charge)

- The Rev. Dallas B. Decker (1987-1990)

- Interim Priests-In-Charge (1900-1992):

- Canon F. Anthony Cayless

- Canon James C. Wattley

- The Ven. Roper L. Shamhart

- The Rev. Patrick J. Holtkamp (1992- )

Zion Church As a Movie Setting

Recollection by Mr. Stuart Hersh

In 1971, when I was a Producer on the WNET-13 program, “The Great American Dream Machine”, I was assigned to film the late W. H. Auden reciting his immortal poem, “The Unknown Citizen”. Although British born, Auden was then a longtime resident of the United States and he was considered by many this country’s Poet Laureate. In fact, many thought of him as, auguably, America’s greatest living poet.

As nobody could read his work with as much feeling and meaning as the author himself, I sought a picturesque setting for the recitation. And, since the poem was a summing up of a man’s life, shortly after his death, what background would be more appropriate than a cemetery. But a graveyard might be, I feared, a rather dismal setting. What I wanted was a beautiful place with striking monuments that spanned many generations. The perfect place turned out to be almost in my own backyard. The churchyard of the landmark Zion Episcopal fit the bill as though it had been waiting for a person of W. H. Auden’s stature to grace it with his living presence. But I could not and would not do it without permission.

If memory serves (it was, after all, thirty years ago), Rev. Burrell was then Pastor of Zion Episcopal. He was thrilled to have the church featured on public television, and he couldn’t have been more helpful. I had spotted an extremely dignified throne-like chair, and on the day of the shoot, he was glad to permit me to have my crew carry it outside and place it in front of one of the stately monuments in the graveyard.

Starting with a tight close-up of the poet’s face as he began reciting his work, we began a very slow zoom back revealing, first, the elegant chair in which he sat, then the fact that he was outdoors, then the tall grave marker behind him, then more gravestones, and as Auden became smaller and smaller in the frame, we continued back to show the entire graveyard and the beautiful church in the background. As his seated figure became a speck in the distance, surrounded by the gravestones of so many Citizens who have passed, Auden’s voice came to the end of the poem. The final scene, viewed by millions, was a lovely one of the beautiful and historic Zion Episcopal Church as it appeared three decades past.

St. Peter’s African Methodist Episcopal Church

St. Peter’s African Methodist Episcopal Church was located east of 243rd Street (Orient Avenue) between 42nd Avenue and Depew Avenue.

A community of black oystermen existed in Little Neck, some as property owners, since the 1850s. While their homes were located outside the Lambertson subdivision (most along Orient Avenue (243rd Street) near the dock at Old House Landing Road), they contributed to community life. Upon the death of oysterman Jacob Treadwell (1833-1904), the Flushing Daily Times reported “He was a well known character in and about Douglaston, where he has been a life long resident”

This community’s church on Orient Avenue, St. Peter’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, was active for over 100 years: founded in 1872, the church building on Orient Avenue held services until the late 1980s. The Hill’s major period of development coincided with the oystermen’s decline, following the 1909 condemnation of polluted Little Neck oyster beds. While their numbers substantially decreased in the early years of the twentieth century, several ancestors resided in Douglaston for many more years.

Site of St. Anastasia Parish’s First Mass

The First Mass offered in Saint Anastasia Parish was in this house on Pine Street (240-16 43rd Avenue). The house was designed by Walter J. Halliday, Jamaica Queens, ca 1909 for the original owner, Adolph Helmus, a paper box manufacturer and member of Douglaston Hose Co. No. 1.

Matinecoc Burying Ground

Members of the Matinecoc Tribe settled in Little Neck and established a burying ground along the north side of the main highway, then called Broadway, between 251st and 252nd Streets in what is now Little Neck. In 1931 when the boulevard was widened, the cemetery protruded out into the roadway. The city obtained permission to remove the remains of the Indians interred in this graveyard and to reinter them in a special plot in Zion Churchyard, in order to straighten the highway.

Fire House / Hose Company

Here’s an image of the old Douglaston Fire House, an Alarm Box sheet, and the Fire House as it is today as the American Legion building. The building stands on Douglaston Parkway (formerly named Main Avenue), west side, between 42nd and 43rd Avenues.

Here’s an image of the old Douglaston Fire House, an Alarm Box sheet, and the Fire House as it is today as the American Legion building. The building stands on Douglaston Parkway (formerly named Main Avenue), west side, between 42nd and 43rd Avenues.

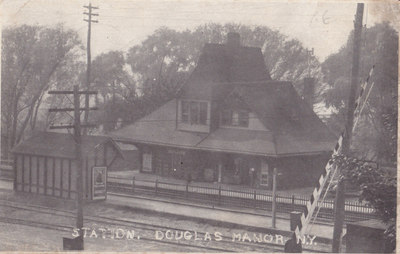

Douglaston Train Station

History of the Douglaston Train Station (Joseph Hellmann, 02/2004: MS Word)

The Flushing & Northside Railroad extended to the Village of Flushing in 1854, and as far as Great Neck, presently Nassau County, Long Island, in 1866. William Douglas donated a farm building from his estate to serve as the railroad station. In exchange, he asked that the station and the village around it be called Douglaston. In 1887, Douglas and resident subscribers funded the Queen Anne-style depot building and landscaping at the new Douglaston station as shown in the picture. Popular postmaster and gardener Albert Benz directed the landscaping project.

The scene is looking North on today’s 235th Street just past Station Realty at about George Martin’s restaurant. To the left is a wooden sign advertising lots in Douglas Manor. Part of the LIRR station roof can be seen just above the sign. Moving right we see the turret of the Van Vleit mansion with its well manicured grounds. It later became PS 98 and stood until the present building was completed in 1931. On the right at the gate is the crossing watchman’s shanty. The track closest is a spur leading to a small freight yard built in 1866 to accommodate the Alley mills. Just below that we can see the first steps of a wooden stairway leading up to the foot of Poplar Street. The ruble stone wall probably dates to a road widening to accommodate the 1906 development of Douglas Manor and can still be seen North of Willow Street opposite the Community Church. The discoloration in the well graded roadway is from oil used to control dust and hold the sand in place during wet weather. Although many believe our cobble stone gutters were constructed by the Works Progress Administration, and no doubt some were, they were actually a common means of controlling erosion dating to colonial times.

By 1961, the Queen Anne-style building had deteriorated to such an extent that the company decided it was not worth repairing, so plans were instigated to have the building replaced.

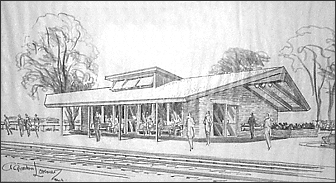

Above is shown the architects conception of the new station which has been erected on the site of the former station building. The plans were developed by a Douglaston resident, A. Gordon Lorimer, whose design was accepted by the Long Island Rail Road Company and the Douglaston residents. The new station was formally opened in 1962 and still stands today.

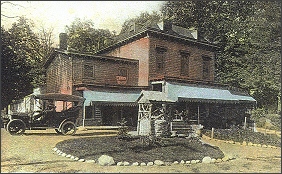

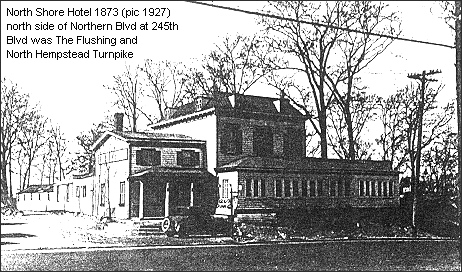

The North Shore Hotel

aka Evan’s Hotel and Douglaston Inn

The North Shore Hotel was believed to have been built c. 1850 1 and was located just east of 247th Street (Lot 75 of Map No. 223 of the village of Marathon) on the Flushing & North Hempstead Turnpike (now Northern Boulevard).

The photographs at right and the large one below show the hotel at three different time periods. They are identified by the names that the business went by at the various times.

Community newspapers chronicle the on-goings at the hotel in some detail:

Flushing Journal 12/13/1890: Drunken vagrant laborer on the North Hempstead Turnpike brought to the North Shore Hotel where he slept in a horse stall.

Flushing Evening Journal 11/6/1897: Proprietors Livingston and Wright report hotel is popular with young people for parties. Henry Snell is having the hotel upgraded with new plumbing and steam heat.

Flushing Daily Times 7/11/1903: Douglaston Hose Company No. 1 celebrates its founding at the hotel now known as Evan’s Hotel.

Flushing Daily Times 10/19/1904 & 11/5/1904: Republican rally takes place at Evan’s Hotel.

Flushing Journal 6/10/1905: Evan’s Hotel filled with summer boarders.

Flushing Daily Times 10/23/1905: Protest meeting concerning proposed school site.

Flushing Daily Times 2/3/1909: Douglaston Civic Association meeting.

Flushing Daily Times 6/17/1909: Dinner given in honor of Norris Mason who worked on a fundraiser for Blessed Sacrament Church in Bayside. Denis O’Leary was toastmaster.

Flushing Evening Journal 1/8/1910: Douglaston Civic Association holds meeting.

Flushing Daily Times 6/13/1910: Civic association meeting again.

In 1915, The hotel was known as the Douglaston Inn. Father Francis J. Uleau, first Pastor of St. Anastasia, held the initial services at the hotel. 2

The Douglaston Inn was closed when prohibition came. It stood idle for some time and was finally taken down in the 1930s 3, most likely during the widening of Northern Boulevard at that time.

Douglaston Art League (Now, National Art League)

The development of a community connected to the city at large is illustrated in the founding and continuity of the Douglaston Art League in 1930, and still active today (now known as the National Art League, located at 44-21 Douglaston Parkway). The League was founded by Mrs. Arthur Sullivan and Miss Helen Chase – sisters and daughters of New York painter William Merritt Chase – along with other residents and north shore artists who were “interested in arousing amore general appreciation of art in the community and in providing a means for practical development of individual talents.” Architect Aubrey Grantham (Zion Episcopal Church) was among the founders. The League’s early exhibits and classes were held in the backroom of a beauty shop and its second show was exhibited in the Parish Hall of Zion Church.

National Art League

In the first quarter of the 20th Century, there existed a thriving arts and theater colony in Douglaston. It included such luminaries as Ginger Rogers, Hedda Hopper, Annette Kellerman, Robert Haggart, George Grosz and many others. A natural consequence of this artistic climate was the establishment of the National Art League (NAL), presently located on Douglaston Parkway. The NAL, originally called the Douglaston Art League (DAL), was founded in 1932. The DAL was the brainchild of the daughters of American Impressionist painter, William Meritt Chase, along with Aubrey Grantham, the architect for the rebuilt Zion Church, James Boudreau, Director of Pratt Institute, and most notably Trygve Hammer, sculptor and wood carver. A naturalized citizen by 1913, Hammer designed rooms for the University of Pittsburgh, the Scofield Memorial Library, and the Waldorf Astoria. Locally, his imprint on the Zion Church remains in his wood carvings there.

The Zion Church has been intertwined with the DAL from the start, not just by virtue of its relationship with the founding members. Reverend Riley is credited with becoming the second patron of the Art League after permitting the exhibition of Chases’s art work at the church. This exhibit caught the attention of the NY Press as well as the art world.

The North Shore Daily Journal, dated November 2, 1933, announced the first exhibit, held at 40-41 Douglaston Parkway, home of the Manor Beauty Salon, and loaned to the DAL by Lucas Mack, making him the first patron of the Art League.

The DAL eventually moved to a location in Flushing, and became known as the Art League of Long Island. Guiseppi Trotta, a portrait painter of men on both the Supreme and New York Bench, lent his studio in Flushing out to the League. Subsequent to the relocation, several articles in the LI Star Journal and Society indicate that the objective of the Art League “to stimulate public interest in the Arts” continued to be met. On February 21, 1948, the Journal reported the addition of painting and sketching from life to its instruction. According to Frank L. Moratz, the director of classes, this resulted in “booming business” for the League. There were published announcements of lectures, and on March 14, 1948, Society announced the opening of the spring exhibition. It should be noted that Mr. Moratz was a mural and portrait painter who also sponsored an exhibit for the Red Cross at Flushing Library. It was hoped that through innovative programs and exhibitions of this sort, the League could continue successfully and might one day have a permanent home.

Louisa Gibala brought this to fruition with her tireless efforts in 1955. The League now resides permanently at 44-21 Douglaston Parkway. In 1968 it established the name that hangs above that address, the “National Art League”.

By: Ellen Dermigny, May 10, 2002

National Art League a Hidden Treasure

From the Queens Ledger*Glendale Register*-LIC/Jackson Heights Journal*Forest Hills Times*Leader/Observer*Queens Examiner, May 24, 2001, page 22

By Judi Willing

Hidden in Douglaston is an organization for serious artists. It is run by men and women committed to the idea that artists need to be nurtured. Whilst the creative process dictates that an artist should primarily create for him/herself rather than for a patron, there is no doubt that the creative process can be stimulated by contact with others – patrons and other artists.

To this end, the National Art League offers a location where successful artists teach, lecture and ‘cheer those that need encouragement.’ In return they are offered the opportunity to learn from other artists, and further their careers by showing their work regularly in exhibition and receive encouragement themselves in the form of awards and prizes.

The National Arts League is a non-profit organization open to all artists and lay members of the public. To join as an artist member, three works of art must be submitted to a judging committee. The annual membership is $25, and artist members can submit works for consideration in the League’s exhibitions and win awards. Last year there were 12 exhibitions in different categories-students, children, members, teachers, photography.

Non-artists can also join for $25 per annum, or at higher levels of sponsorship. Members can enjoy classes in watercolors, oil or mixed media (acrylic, collage and sculpture) – $15-20 per 3 hour class during the day or evening. There is a library, group trips to galleries, and studio space available. There are special workshops where artists talk about their methods and techniques. There is a course starting in graphic design, probably in September.

Currently the Spring Open Exhibition can be viewed. On Sunday May 20, 2001 between 1 and 4pm, there will be a reception for the artists, and awards given. The National Arts League is at 44-21 Douglaston Parkway, Douglaston, NY 11363. Telephone 718 224-3957. E-mail: artworknal@aol.com

Website: www.nationalartleague.org. If you are seriously interested in art, the National Art League is interested in you, and can offer a lot in return.

Catherine Turner Richardson Park

The Little Neck School Annex

The Early Schools

PS 32 Annex, (1910/1920)

Located in Catherine Turner Richardson Park, at 42nd Avenue and Douglaston Parkway. This school was a branch of PS 32 located at Little Neck Parkway and Lakeville Road. It was established to serve the growing Douglaston community.

PS 98 (Provisional) (1920/1931)

Continuing growth required a move from the Annex to this building. Located on the present site of PS 98, (Douglaston Parkway and Willow Street). It had been the previous home of Clinton Van Vleit, an executive with Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co.

Noteable Residents

Julian Caplan, Attorney & Mark Twain Impresario

Gertrude Moll, Suffragette activist

John McEnroe, Tennis Champion

Ed Lauter, Actor

Arthur Treacher, British Actor

Ralph Batcher, Telecommunications Inventor

John Cannella, Federal Judge, Football Player

Building Survey